The long, shameful road to a new women’s prison

The 30-year wait for a new facility represents a moral failure by the Legislature

It is strange to say it’s great to see a new prison, but in the case of the NH Women’s Prison, this statement rings true.

The new prison will have vocational and educational programs and access to 24/7 health care services on site. There will be treatment for inmates with mental health and substance abuse problems. The programs and services will be comparable to those for male inmates.

While Alan Linder and Elliott Berry, two New Hampshire Legal Assistance lawyers who worked on the class-action lawsuit on behalf of the women state prisoners have been justly praised for their work, that’s only part of the story.

The saga actually began in 1983, when Bertram Astles, a private attorney and later with New Hampshire Legal Assistance, filed a class-action lawsuit claiming that the state of New Hampshire was violating the constitutional rights of women state prisoners to equal protection of the law.

In the early 1980s, there was no women’s state prison, and New Hampshire was shipping women prisoners to other states, as far away as Maryland, Colorado and South Carolina. Many of the women were held in prisons in Massachusetts, especially MCI-Framingham, while some landed in county jails in New Hampshire. Back then Framingham was no picnic — it was hard time.

The women had no control where or when they would be sent away. If they stayed in New Hampshire in a county jail, it was basically solitary confinement. The counties offered nothing, not even outside exercise.

As a law student at Franklin Pierce Law Center (now UNH Law), I interned at NHLA in 1983-84 and helped out on the women’s prison case. I traveled to Massachusetts prisons to meet with and interview the New Hampshire women, and I took their affidavits where they told their stories.

The women were far from their families and lawyers. Lack of communication and isolation contributed to depression.

Many of the women were young mothers and they grieved the separation from their children, whom they rarely if ever saw. The impact of a mother’s incarceration on children was not considered by state officials.

Women at in-state county jails had their own special hell. The county jails were not set up for long-term inmates, and they had no programs or services for the women. If a vacancy opened in an out-of-state prison, the women would get shipped out with no notice.

During my internship, I also witnessed the battle over the halfway house. Unlike the men who had a halfway house next to the state prison, the women had no facility to ease their transition back into society.

The halfway house was integral to the path for parole. The vocational and educational programs were not just filling time. Without a job and a place to live, the women brought nothing to the parole board. They needed those programs and the halfway house to show progress since it was a ticket out. Without the halfway house, women were stuck.

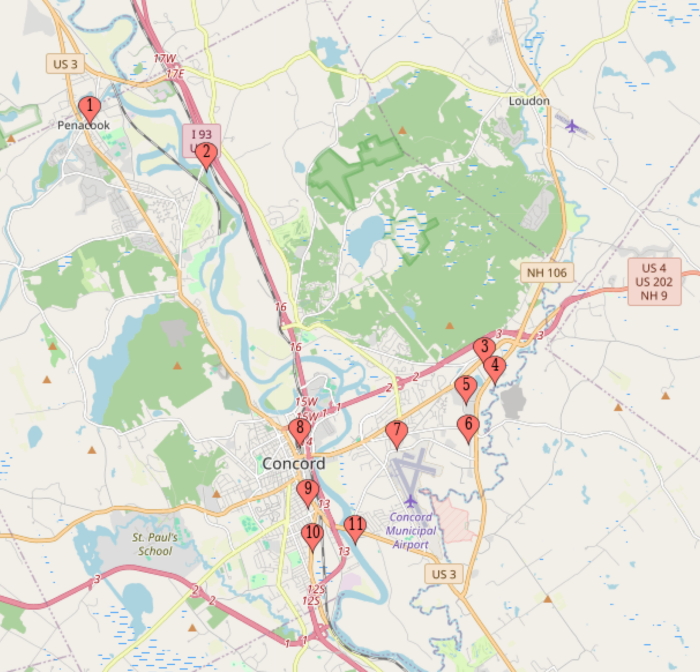

The state’s failure to have a halfway house looks like rank sex discrimination now, but at the time the case was no slam dunk. The morning of the preliminary injunction hearing in federal court in Concord, none of the women prisoners showed up to testify. There was a problem with the orders of transport. Still, the Attorney General’s Office ranted like the case was frivolous.

Fortunately, the plaintiffs had some aces up their sleeve. NHLA had an awesome trial prison expert, Edyth Flynn, who testified persuasively and exposed the state, as well as excellent trial counsel — Alan Linder an Alice Schierberl, a Portsmouth-based Legal Assistance lawyer. Both were passionate and effective advocates.

The plaintiffs were very fortunate to have U.S. District Court Judge Martin Loughlin hear the case. He was a down-to-earth, compassionate man who had a soft spot for the down-and-out. Even without the plaintiffs themselves testifying at the preliminary injunction hearing, he ruled in their favor. Later, in the trial on the merits, he also ruled for the plaintiffs.

It was Judge Loughlin’s initial finding in 1987 that the state violated equal protection that tipped the balance and moved the case forward. Judge Loughlin ordered the construction of a permanent, in-state prison for plaintiffs no later than July 1, 1989. Although that 1989 date was not to be, Judge Loughlin’s role was critical. His ruling created the inevitability of an in-state prison for women.

Instead of building a new prison, the state stuffed women prisoners into the former Hillsborough County House of Correction in Goffstown, a cramped and antiquated facility that was never intended for long-term use as a prison. There was almost no space available for basic vocational training or mental health treatment. Space was lacking for even family visitation.

After 1989, report after report was issued about the inadequacies of the Goffstown facility, including one from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. A 2009 report of the Interagency Coordinating Council for Women Offenders shockingly reported that only two women had received high school diplomas during the two decades the Goffstown women’s prison had been in operation.

This abysmal record forced NH Legal Assistance to file a second class action in 2012 because the state failed to live up to its obligations.

In considering the history, I blame New Hampshire state government, particularly the Legislature, for its failure to spend money on behalf of the women prisoners. The Legislature’s procrastination and refusal to fund was not just a moral failure. It reflected blatant sexism and disrespect for the law. Judge Loughlin’s order was ignored, causing untold harm to the women prisoners. Amazingly, we are now three decades beyond his ruling and the question still must be asked: Why did it take the state so long to do the right thing?

Jonathan P. Baird of Wilmot works at the Social Security Administration. This article reflects his own views and not those of his employer.